Cycle 1948-1951

According to FIDE’s plan approved in 1947, the first Interzonal was scheduled for 1948. Among the participants included the winners of the Zonals: O’Kelly (BEL), Kashdan (USA), Yanofsky (CAN) and BOOK (FIN). The list will be completed with an invited player list, which was lead by Najdorf(ARG), Boleslavsky (URS) and Stahlberg (ARG). Twenty players with the top five to have right to play a final tournament in 1949 with Smyslov, Reshevsky, Keres, Euwe and Fine.

Interzonal

The tournament opened on July 16 in Salsjbaden near Stockholm with the expected participants excepted O’Kelly (BEL) and Eliskases (ARG) who were replaced by Pirc (YUG) and Lundin (SWE).

In the opinion of many , his tournament was one of the strongest competition played until then despite that many players qualified like the American could not arrive due to…financial difficulties.

At mid-stage or after 10 rounds, Szabo from Hungary and Bronstein from USSR were leading with 7 points following by Lilienthal (HUN) and Najdorf 6½. Szabo took sole the lead from the next round and kept it until round 18 when again Bronstein came back to share the pole position. At the final round, Szabo was paired with Lundin who was the weakest player of the tournament. Incredibly, the Hungarian with a better position made a faulty combination and lost a lot of material when at the same time Bronstein concluded brilliantly against the French Tartakover. Bronstein called “little David” was born in 1924 near Kiev. He didn’t win so far major tournament but can claim a plus score against Botvinnik, Smyslov and Keres! This first great victory was also his first tournament outside of USSR.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | Total | ||

| 1 | Bronstein, D | Xx | 1 | ½ | 1 | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | 1 | ½ | ½ | 1 | ½ | 1 | ½ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 13.5 |

| 2 | Szabo, L | 0 | Xx | ½ | ½ | 1 | ½ | 1 | ½ | ½ | 1 | ½ | 1 | 1 | 1 | ½ | 1 | ½ | ½ | 1 | 0 | 12.5 |

| 3 | Boleslavsky, I | ½ | ½ | xx | ½ | ½ | ½ | 0 | 1 | ½ | 1 | ½ | ½ | 1 | ½ | ½ | ½ | 1 | 1 | 1 | ½ | 12.0 |

| 4 | Kotov, A | 0 | ½ | ½ | xx | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | 1 | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ½ | 11.5 |

| 5 | Lilienthal, A | ½ | 0 | ½ | ½ | xx | 1 | 1 | ½ | ½ | ½ | 0 | ½ | ½ | ½ | 1 | ½ | 1 | ½ | ½ | 1 | 11.0 |

| 6 | Bondarevsky, I | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | 0 | xx | ½ | ½ | 1 | 0 | ½ | 1 | ½ | 0 | ½ | ½ | 1 | ½ | 1 | 1 | 10.5 |

| 7 | Najdorf, M | ½ | 0 | 1 | ½ | 0 | ½ | xx | ½ | ½ | 1 | 0 | 1 | ½ | 0 | ½ | 1 | ½ | ½ | 1 | 1 | 10.5 |

| 8 | Stahlberg, G | ½ | ½ | 0 | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | xx | ½ | 0 | ½ | 1 | 1 | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | 1 | ½ | 1 | 10.5 |

| 9 | Flohr, S | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | 0 | ½ | ½ | xx | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | 1 | ½ | 1 | 1 | 10.5 |

| 10 | Trifunovic, P | ½ | 0 | 0 | ½ | ½ | 1 | 0 | 1 | ½ | xx | ½ | ½ | 0 | 1 | ½ | ½ | 1 | ½ | 1 | ½ | 10.0 |

| 11 | Pirc,V | 0 | ½ | ½ | 0 | 1 | ½ | 1 | ½ | ½ | ½ | xx | ½ | ½ | 0 | 1 | 0 | ½ | 1 | ½ | ½ | 9.5 |

| 12 | Gligoric, S | ½ | 0 | ½ | ½ | ½ | 0 | 0 | 0 | ½ | ½ | ½ | xx | 1 | ½ | 1 | 1 | 1 | ½ | 0 | 1 | 9.5 |

| 13 | Book, E | ½ | 0 | 0 | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | 0 | ½ | 1 | ½ | 0 | xx | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9.5 |

| 14 | Ragozin, V | 0 | 0 | ½ | ½ | ½ | 1 | 1 | ½ | ½ | 0 | 1 | ½ | ½ | xx | 0 | 0 | ½ | 0 | ½ | 1 | 8.5 |

| 15 | Yanofsky, D | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | 0 | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | 0 | 0 | ½ | 1 | xx | 0 | ½ | ½ | ½ | 1 | 8.5 |

| 16 | Tartakower, S | 0 | 0 | ½ | 0 | ½ | ½ | 0 | ½ | ½ | ½ | 1 | 0 | ½ | 1 | 1 | xx | 0 | ½ | ½ | ½ | 8.0 |

| 17 | Pachman, L | ½ | ½ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ½ | ½ | 0 | 0 | ½ | 0 | ½ | ½ | ½ | 1 | xx | 1 | ½ | 1 | 7.5 |

| 18 | Stoltz, G | 0 | ½ | 0 | 0 | ½ | ½ | ½ | 0 | ½ | ½ | 0 | ½ | 0 | 1 | ½ | ½ | 0 | Xx | ½ | ½ | 6.5 |

| 19 | Steiner, L | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ½ | 0 | 0 | ½ | 0 | 0 | ½ | 1 | 0 | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | xx | ½ | 5.5 |

| 20 | Lundin, E | 0 | 1 | ½ | ½ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ½ | ½ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ½ | 0 | ½ | ½ | xx | 4.5 |

The FIDE Congress was also scheduled in Saltsjobaden. Both Argentina and Hungary bided for the Candidates’ Tournament but the each one with one condition. The Hungarian could no cover the player’s traveling expenses and the Argentinean want Najdorf and Stahlberg to play. Despite the fact than the majority of the members preferred the South American choice, the Soviets made huge pressure on the Assembly saying that they were doubtful about the willingness of their players to travel so far…! Passion took over and treats of break-up FIDE was even declared. Finally, the assembly approves a presidential’s proposal to set up a commission in view to settling the matter. It was also decided to increase the number of participants to the Candidate’s Tournament to 14. So the first nine of the Interzonal were qualified.

Despite the announcement of FIDE begin of 1949 to hold the Candidates’ Tournament in Buenos Aires, the Soviets imposed a vote of confirmation in the FIDE 1949 Congress which was held in Paris. Curiously (mainly because of the threat than no Russian will attend the tournament) the previous decision was outvoted and Budapest became the official venue to select the winner to play Botvinnik in 1951.

An elaborate system of rules has been governing future world championship arrangements:

(i) Every third year, a competition either a match or a tournament- will be organized for the world championship.

(ii) The winner of the FIDE Candidates’ Tournament is entitled in the forthcoming year to play a match against the world champion for the championship.

(iii) If the world champion cannot or will not defend his title the year following the candidates’ tournament, the match will be played instead between the two masters who, in the candidates’ tournament, have won the first and second places.

(iv) If the winner of the candidates’ tournament does not use the right to challenge the champion, the player who won second place has the right.

(v) If the champion and the challenger cannot agree about the match terms, a tournament will be arranged between the champion, ex-champion and the players who won the first and second place in the candidates’ tourney.

Decisions (vi) and (vii) apply to rights of ex-champions.

(viii) Applies to absent candidates.

(it) If the world champion ties in a championship match, or shares first place in a championship tourney, he retains the title.

(x) The right to organize a world championship competition is, in the first instance, the right of the federation of the champion’s country if the champion himself participates.

(xi) In a world championship match, 24 games shall be played. When one of the players reaches 12½ points, he shall be declared the winner. A world championship tournament shall consist, with four participants, of six rounds (one round consists of one game against each participant) and with three participants, ten rounds.

(xii) In a world championship competition, 3 games a week should be played in such an order that the adjourned games can be continued the following day. For the first 40 moves, 2½ hours each shall be allotted and the game shall be adjourned after a total playing time of 5 hours. Adjourned games shall be played at a rate of 16 moves per hours each.

(xiii) Illness right is defined.

(xiv) Each contestant in a world championship competitor shall have the right to have a second. Only a second has the right to assist n analyzing adjourned games.

(xv) In a championship match, the victor shall have an honorarium of US$ 5,000 and the opponent US$ 3,000.

First Candidates’ Tournament 1950

The first Candidates’ Tournament was held in Budapest in April-May 1950. For different reasons Reshevsky, Fine and Euwe canceled their participations. For Euwe, it was because for teaching duties and for both Americans players because the US Department of State banned US citizens from entering to Hungary.

With the Americans forced to abstain, C&R published in March 1950 an article on the Russian to control FIDE decisions: “…The Russian have argued that they should have the principal voice in determining the choice of the site and presumably thereafter of playing conditions. Such an outcome would be manifestly unfair. The roll of contenders is heavily weighted with Soviets players…

FIDE had once more to readjust the number of entries with the top nine of the last Interzonal without Bondarevsky ill, plus Smyslov and Keres who were qualified by regulations.

(BCF) At Budapest, this was enormous thousands of spectators attending every day. From the first, it was evident that the Russian contingent not only outnumbered but also outclassed the remaining three players. Though Stalhberg twice struck shrewd blows against two of their leaders by boating Bronstein and Smyslov, he could not keep up this form consistently. Here I should add that, however regrettable from the sporting point of view was the absence of the two R. Fine and Reshevsky, I doubt very much whether their presence would have affected the final result a great deal. For stern, hard practice against the formidable opposition is essential for success in a tournament of this caliber, and it is exactly this that the U.S.A. players lack. Mystical talk about the affinity for chess, of the Slav temperament is quite unnecessary. The great strength of Russian chess derives from the iron-hard practice their players get; theirs truly is a fortunate, rather than vicious, circle in which strength breeds strength in ever increasing degree. . –

Boleslavsky started with an Impress powerful victory against Flohr played in the massive style that characterizes him when at top form. His sureness of touch never once deserted him and It was no accident that he was the only player to go through the tournament without a loss. Bronstein, on the other hand, adopted quite a different policy. In marked contrast to his cautious pIay at Stockholm, 1948 he threw discretion to the winds, took chances with, indeed, success, and despite a loss to Smyslov in Round 2 was one of the three leaders at Round 7, with 4½.

The third was Keres who had been playing with great circumspection in an attempt to banish the bogy of uncertain form that has been afflicting him of recent years. With rare brilliant exceptions, he built up his position with immense care, winning an endgame and for the rest being content to let the draw come when it would. Such a plan of campaign demands, not only immense patience but great physical stamina, and it was this that let Keres down towards the end.

In the 8th round, Boleslavsky assumed the sole lead by a crushing victory over Kotov, whilst Keres could do no more than draw with Lilienthal and Bronstein was beaten by Stahlberg. This lead he enjoyed to the very last round. He had a wonderfully successful run from the 6th to the 14th round during which he scored 6-points. Even more remarkable, however, was the finishing run of Bronstein, who extracted 7 points out of the last 8 rounds, and by a brilliant victory over Keres in the very last round just managed to overhaul Boleslavsky. This tie means that sometime this year there must be a match between the two winners to decide who shall meet Botvinnik next year.

Smyslov’s third place, though achieved by rather up and down form, is still a most creditable achievement and Keres would have been a great challenge for the two leaders if he had been able to stay the pace. Najdorf never looked like a real menace to the top players, being apparently content to attain a satisfactory position and to avenge himself thoroughly for losing a brilliancy prize game to Lilienthal at Stockholm, 1948, by twice trouncing that unfortunate grandmaster here.

Kotov seems to be developing into the Frank Marshall of Soviet chess and is just as likely to lose as to win brilliantly. He is almost too aggressive for consistent success. Stahlberg played some beautiful games but lacked that powerful sureness that was so marked in Boleslavsky and like Najdorf never seemed a challenger for the top place. Lastly, we come to the unhappy three tailenders.

Very surprising was Szabo’s weak form. He seemed to lose heart early on and then to succumb repeatedly in a wretched style quite aliens to his normal self. I believe this is only a temporary lapse and that he will yet show how -truly formidable he is in future tournaments. The same cannot be said for either Flohr or Lilienthal both of whose stars are now quite clearly on the wane.

Confirmation of what has been said above about the various styles of the players can be found by studying their scores. Bronstein won the most games—eight—an astonishing number in such a tournament. Keres drew most—thirteen—just noting Flohr out of his usual place by one; whilst it was Szabó’s not a very invidious distinction of losing most seven.

At the end of the first half of the tournament, the Magyar Sakkvilog interviewed various competitors who made co remarks about the tournament organization. Here are two of the interviews, translated from that magazine.

Stahlberg: “I am thoroughly satisfied with everything, even with my own play. I was a little lucky against Bronstein and Lilienthal, but on the other had rather bad luck against Keres and Najdorf. In general, the players seem nervous, and the last half hour of the session is usually a desperate rush in time trouble, but despite the numerous draws, the play has been interesting and adventurous, and there has been no dull wood shifting.

“Boleslavaky’s success is well deserved; with the exception of his game against Keres he has never stood in any danger, and almost always held the advantage. Keres has played solidly and risked little but has given a glimpse of his combinational talents in his game against Kotov. Bronstein plays the most aggressively, perhaps here and there a little too much so. So far Smyslov has not been in his best form, we can expect more from him in the second half. Najdorf is playing very nervously and inconsistently. Kotov has shown some good ideas, whilst Szabó has been a disappointment he has played sharply and risked too much. Also, Lilienthal and Flohr have not shown their best sides, though Lilienthal has pulled up a good deal towards the end.”

Najdorf: “The arrangements are wonderful, the chess players are surrounded by the utmost peace and calm, though, unfortunately, they do not often play accordingly. The reason for this resides in the fact that there is really only one high prize the right to play against Botvinnik for the world championship. This circumstance is a novel one and renders everybody nervous, and I believe that nobody has quite played up to the expected form.

‘For example, Smyslov has committed numerous blunders, even big ones. This arises from the numerous fighting games that can be observed, despite a large number of draws, and in such games, it is easy to blunder. Boleslavsky has committed the least mistakes and has, therefore, merited his first place so far. Bronstein has played the most aggressively but has not been favored by fortune since he lost to Stahlberg in a better position.

“Szabó, also a candidate for the first place, has been a disappointment in his hometown. He is really a very great player but unfortunately, cannot endure losses. In his very first game, he was crushed by Bronstein, and this demoralized him; hence both against me and Lilienthal, he failed to show his tried capabilities.

‘Alas. I myself have not played well, perhaps I will do better in the second half. My openings have been well played and I have often attained a winning position, which, nevertheless, I have been unable to win: this shows I am not in form. flj In the two games I lost to Bronstein and Smyslov was below criticism, but the tournament is, of course, not yet finished.”

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Total | ||

| 01 | Bronstein, D | Xx | ½ ½ | 0 1 | ½ 1 | 1 1 | 1 ½ | 0 1 | ½ ½ | 1 ½ | ½ 1 | 12.0 |

| 02 | Boleslavsky, I | ½ ½ | xx | 1 ½ | ½ ½ | ½ ½ | 1 ½ | ½ ½ | ½ 1 | ½ 1 | 1 1 | 12.0 |

| 03 | Smyslov, V | 1 0 | 0 ½ | xx | ½ ½ | 1 ½ | ½ 1 | 0 1 | ½ 1 | ½ ½ | ½ ½ | 10.0 |

| 04 | Keres, P | ½ 0 | ½ ½ | ½ ½ | xx | ½ ½ | 1 0 | 1 ½ | ½ ½ | ½ 1 | ½ ½ | 9.5 |

| 05 | Najdorf, M | 0 0 | ½ ½ | 0 ½ | ½ ½ | xx | ½ ½ | ½ ½ | 1 1 | ½ 1 | ½ ½ | 9.0 |

| 06 | Kotov, A | 0 ½ | 0 ½ | ½ 0 | 0 1 | ½ ½ | Xx | ½ 1 | 1 0 | 1 0 | 1 ½ | 8.5 |

| 07 | Stahlberg, G | 1 0 | ½ ½ | 1 0 | 0 ½ | ½ ½ | ½ 0 | Xx | ½ ½ | ½ ½ | ½ ½ | 8.0 |

| 08 | Lilienthal, A | ½ ½ | ½ 0 | ½ 0 | ½ ½ | 0 0 | 0 1 | ½ ½ | Xx | 1 0 | ½ ½ | 7.0 |

| 09 | Szabo, L | 0 ½ | ½ 0 | ½ ½ | ½ 0 | ½ 0 | 0 1 | ½ ½ | 0 1 | Xx | 1 0 | 7.0 |

| 10 | Flohr, S | ½ 0 | 0 0 | ½ ½ | ½ ½ | ½ ½ | 0 ½ | ½ ½ | ½ ½ | 0 1 | Xx | 7.0 |

Playoff

So by regulations, the two first winners of the Interzonal Boleslavsky and Bronstein and Boleslavsky went to play a match in Moscow to decide the winner of the cycle. The best twelve games had been intended but when these had been completed the score was still even. FIDE had provided that, in the event of a tie, two more games has been completed and if the players remained equal, the match would continue until one player will score a win. The thirteenth game was a draw but in the next Bronstein with that flash of psychological genius which has, on many occasions, served him in good stead, played a move in the French defense condemned by all the analysts. Boleslavsky taken by surprise failed to find the right reply and Bronstein emerged triumphantly. Bronstein managed to win the match 7.5-6.5 and to become the official challenger to play M. Botvinnik for the World championship title.

In his biography published in 1995, Bronstein remembered the Candidates’ tournament:” During the Budapest Candidates’ Tournament Boleslavsky and I had discussed the chances of the next challenger and my friend, who had lost seven games to Botvinnik without winning a single one, was of the opinion that a fight against Botvinnik was hopeless Once he had had a chance to checkmate Botvinnik in a few moves but missed the opportunity.

Of course, I had a completely different opinion. I argued that Botvinnik was very strong but one could still play against him successfully. I was sure that I could demonstrate that his strategy was far from perfect.

Isaac Boleslavsky was leading in the Candidates’ Tournament but after a talk, he had with Boris Vainstein he decided to slow down to allow me to tie for first place with him. Vainstein would try to arrange a tournament with Botvinnik, Boleslavsky and myself for the World Championship. Alas, it did not come about and we had to meet in a play-off for the right to challenge Botvinnik.

The whole atmosphere in the Soviet chess world was that Botvinnik was the best player during the last two decades and he deserved the title of World Champion. One was almost afraid to take it away from him!

In the match with Isaac Boleslavsky, I was successful in the first and in the seventh games. I also had an easy win in the fifth game but made some weak moves after the adjournment and the game ended in a draw. It was in the sixth game that I played the famous Marshall Attack in the Spanish Opening and managed an easy draw with Black. Then I started to play less strongly and after 12 games, the score was 6-6. We played a very sharp 13th game and while playing through the moves it should be clear that neither of us was too much concerned about the final result. I did not care about Black’s passed pawns and Black very freely sacrificed his Queen for my Knight. The match was decided in game 14 after Boleslavsky repeat the sacrifice of the pawns from game 12; in the meantime had fond the refutation in a home analysis.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | Total | |

| Bronstein, D | 1 | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | 1 | 0 | ½ | ½ | 0 | ½ | ½ | 1 | 7.5 |

| Boleslavsky, I | 0 | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | 0 | 1 | ½ | ½ | 1 | ½ | ½ | 0 | 6.5 |

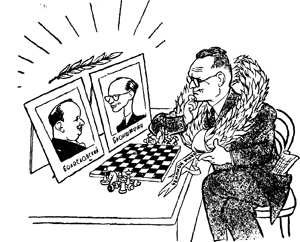

The Final

When the time came to defend his title against David Bronstein in 1951 he had not played in a tournament for three years. But his serious approach to his task remained the same. Botvinnik took a good six months’ leave of absence — to prepare himself. This time, however, he was facing a dedicated artist who knew nothing of ‘spare time’ and devoted himself to chess more than any other of Botvinnik’s rivals. Days of analysis and nights of ‘unprofitable’ play had made Bronstein a formidable exponent. In other words, Bronstein, winner of the first Candidates’ Tournament, was the better prepared.

Botvinnik underestimated the danger of this meeting with Bronstein. In fact, he hadfacedg him in an exceptionally experienced player and a daring psychologist. Bronstein had aroused the enthusiasm of the chess world by his astonishingly rapid rise and his creative imagination.

David Bronstein was the youngest of the Soviet grandmasters. Born in Kiev in 1924, he scored his first major victory in the Moscow championship of 1946 ahead of Bondarevsky, Kotov, Lilienthal and Smyslov and he followed this up by taking third place in the All-Union Championship. In the next two championships he finished equal first with Kotov and Smyslov respectively. Personally Bronstein is a likeable and highly cultured young man entirely lacking I foibles that it is a real pleasure to play against or to meet socially. He is a student in English literature and a lover of Shakespeare.

The match commenced on March 15th at the Moscow at the Tchaikovsky Salle in Maikovsky Square.

Bronstein was the first leader. After 4 draws he won game 5. However Botvinnik recovered very well by winning the next two games and take the lead. At the middle stage Botvinnik was still plus one. Then his play became very disappointing. The fact that Botvinnik didn’t play any top tournament since he won in 1948 had something to do with his performance. Bronstein played at his best but he shows great weakness in ending like for instance in game 19th or in the 23rd game when he missed 43…Na7 with good chance to draw.

In the last two games Botvinnik leveled the score by winning a decisive 23th game. The final result was a tie, 5-5 with 14 draws. As per regulations (like in 1910 wiht the match Lasker-Schlechter) the champion retained his title.

For the statisticians Black won six games to White’s four games. The Dutch Defense were used 7 times and proved to be very reliable. 1.e4 was play only three times. The shortest game (24th) was a draw in 22 moves and the longest (16th) was 75 moves.

At the concluding press conference, Botvinnik declared that he was going to study the games deeply as he was not satisfied with his play. “I came to the game badly prepared, lacking in ideas and the ideas I produced came as result of arduous time-consuming thought over the board.”

Game 1

Dutch Defense.

Like Euwe did it to Alekhine in 1935, David Bronstein as Black turned to a defense favored by World Champion Botvinnik who sprang a new move 6. e3. He had Botvinnik under severe pressure but finally resorted to repetition of move rather than risk loss himself under the time-limit, to draw in 29 moves.

Game 2

Gruenfeld Defense.

Bronstein once more outplayed the Champion. As White he tried a comparatively little-analyzed sub-variation. Bronstein obtained a superior position on move 15 and Botvinnik lost considerable time in planning a defense and so got into trouble. Bronstein missed a Rook’s sacrifice for a centrally posted Knight which gave him a strong counter-play. After a questionable 37th move White decided to go for draw.

Game 3

French Defense (Tarrasch Var.)

Botvinnik pressed Bronstein with Black for the first time, despite some no consequence inaccuracies but the game went to an endgame Knight vs. Bishop which slightly better for White. Finally the Champion messed up and the game was draw in 63 moves.

Game 4

Slav Defense

Botvinnik with Black adopted an old variation of the Slav played often by Flohr and soon got into unpleasant passive position. The Champion hold firm and simplify the complex position to reach an endgame of opposite color Bishops which was concluded as a draw in 47 moves.

Game 5

Nimzovich Defense.

The first decisive break came as Bronstein (Black) picked up a Pawn and the advantage later in the game. Botvinnik over-estimated his chance and went into serious trouble after 30. Rd1 instead of 30.Ke7 following by 31. Nd5 with equality. Bronstein didn’t missed the opportunity and after 30…Re8!! he catches the advantage and brilliantly went to win in 39 moves.

Game 6

Sicilian Defense.

Botvinnik as Black held firm through the first session as Bronstein was by far the most active player but could not claim a decisive advantage. In the second, Botvinnik was a pawn down but got an active King, Bronstein took a lot of risk and tragically blundered in a totally equal position. He immediately resigned alter his 57th move.

Game 7

Catalan System.

Bronstein didn’t recover the tragic outcome of the previous game and Botvinnik as White wore down once more Bronstein. He challenger stood well in the Dutch defense used already in game 1 but after h reached a drawish position he lose his patience Intent on the Queen side, he lets a Kings-side Pawn fall for no obvious reason. At some stage Botvinnik took a Pawn the wrong way but Bronstein overlook that fact and went to a second session with a hopeless Knight and Pawn endgame in which he finally resigned after 66 moves.

Game 8

Queen Pawn Opening.

Botvinnik defended as Black in a theoretical Slav-Meran defense, Bronstein has the usual better game with two connected Pawns flying on the Queen-side. Black balanced with a strong center and watching any Pawn advance. Draw was reached after simplification. (40 moves).

Game 9

Dutch Defense.

Botvinnik as White pressed Bronstein into time-trouble and picked up a full Rook for one Pawn. Instead to consolidated his position the Champion squandered material and arrived at an endgame in which his extra Bishop is nullified. Then missing chances he took only a disappointing draw in 42 moves.

Game 10

Dutch Defense.

Not much reported except that Bronstein missed his 29th move and the blunder which could decide on the issue of the game was not exploited by his opponent who missed 30..Nxf4 wining pawn and maybe the game. A draw after 55 moves.

Game 11

Queen’s Indian Defense.

Bronstein, though Black (neither wins with White!), evened the match by defeating Botvinnik, apparently in less than 40 moves. He chose an opening usually use by his opponent and got soon an unassailable position. White sacrificed two central Pawns to secured an attack which vanished once the Challenger decided to launch a successful and devastating counter-attack.

Game 12

Dutch Defense.

The pattern of this game was similar to the 11th. Bronstein as White sacrificed 2 Pawns to build an attack but good defense by the Champion push back all hopes of concretization. Bronstein subsequently tried to maintain his attack by more sacrifice and Botvinnik readily accepted two Pawns and the exchange to win easily and retake the lead.

Game 13

Nimzo-Indian Defense.

Like in game 5 but this time with the Knight in e2, both players debated an opening which gives an usual little plus for the white pieces. Black was cleaver to simplify at the right time and after 20 moves the tension vanished completely and even the white’ extra Pawn had no value to claim for a win. Draw in 56 moves.

Game 14

Tchigorin Defense

Slow start with a completely closed position when the first exchange occurs at move 17 and the first pawn to go came at move 22. Botvinnik was like a fish in water. At the right moment after a careful preparation he stroked on the Queen-side and emerged with an extra apwn. Not enough however to avoid a later draw.

Game 15

French Defense

Similar scenario to the third game, Bronstein decided to retain his King Bishop and heads for the endgame. The weakness of an isolated pawn made him in uncomfortable situation. When the time came to pick up this weak Pawn, the Champion overlooked a tactical finesse and has to take a draw.

Game 16

Game 17

Nimzo-Indian Defense

Another Black victory for the Challenger. This time he win a fine positional play. He put pressure in the center and advance his King-side Pawns to break through Botvinnik’s defense. The Champion missed some counter-chances and instead choose and entire hopeless line. His subsequent blunder simply shortens the game.

Game 18

Slav- Meran Defense

A tiring game which ended after 57 moves. Botvinnik tried to avoid to open lines and positions where Bronstein excelled in it and therefore commit himself to passivity. White got his chance near the end of the middle game with a sacrifice he obtained few dangerous passed Pawns. But in a very complex position and uncertain about the issue of his game, White eventually has to settle for a perpetual check.

Game 19

Neo-Gruenfeld Defense

Another speculative win from Botvinnik. Once more Bronstein showed some accuracy in his endgame play. It is not clear to explain how he missed a so easy way to draw the game when the move 42…Nxa4!! was expected by most all the attendance. Instead he went on into hopeless line and finally gave up after 60 moves.

Game 20

Reti Opening

Bronstein with white didn’t produce too much and could be happy that black’s initiative didn’t concretize into a full point. Hopefully he managed to simplify the position to enter into an even ending which was easy to hold.

Game 21

King’s Indian Defense.

Bronstein with Black was delight to play his favorite opening and therefore perform a masterpiece. He deviated from the usual line which see Black attacking the King-side and instead launch his assault on the Queen-side. White very passive could avoid a Black rollup and gave up the advantage, a pawn and the game in 64 moves.

Game 22

Dutch Defense

The game was a pretty much repetition of the game 16 but with two improvements by Bronstein. The home work made Botvinnik into serious difficulties with his f-pawn and his King-side weakness. Playing very precisely Bronstein maximized his advantage with 34. Bh4 and buried his opponent with 37. Bg3 threatening mate in two or three moves. One point ahead, Bronstein need two draws to win the title

Game 23

King Indian Defense

This game will stay long in the chess history. Bronstein never play for draw and his lack of experience at such level made him probably to lose a potential title. Were some external pressures involved? No sure however what it was clear as we could see in the games so far played is that the endgame was the part of the game where he could claim superiority on Botvinnik. The chose of the opening was not questionable however the strategy used asked questions. Living Botvinnik into a endgame with two Bishops was like a nice gift for the champion. The Champion excelled in such endgame and once more he proved that in endgame two Bishops are more than often superior to two Knights. With great skill Botvinnik equalized and probably safe his title.

Game 24

The shortest game of the match but Bronstein tried hard to get the point. He sacrificed two Pawns with the idea to overthrow the Black fortress. The Champion defended well without to give a single inch of chance to his challenger. Finally with a Pawn up and a solid position the Champion offered a draw that Bronstein accepted immediately.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | Total | |

| Botvinnik, M | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | 0 | 1 | 1 | ½ | ½ | ½ | 0 | 1 | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | 0 | ½ | 1 | ½ | 0 | 0 | 1 | ½ | 12.0 |

| Bronstein, D | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | 1 | 0 | 0 | ½ | ½ | ½ | 1 | 0 | ½ | ½ | ½ | ½ | 1 | ½ | 0 | ½ | 1 | 1 | 0 | ½ | 12.0 |

In his biography, Bronstein gave some though about the outcome of the match: “Playing for the title of World Champion is the dream of every chess player but deep inside me, subconsciously, I must have had no real ambition to win. Otherwise I can not explain why I did not win the match when, only two games from the end, all the odds were in my favour.

After the match Botvinnik himself gave evidence to this opinion despite the result of 12-12 and the obvious fact that he saved his title only in the last game, he simply explained his ‘bad’ result like this: ‘I have not played chess for three years. This is why I played below my normal strength but my opponent is a good player. He is particularly strong when the game is transforming from the opening to the middlegame and in addition he conducts an attack against the enemy king very well.’

Botvinnik did not explain why, during almost two months of play, he did not succeed in winning a single game during the first five hours of play. Four out of his five wins were achieved after the adjournment. I lost three completely even end- games as a result of bad homework. On the other hand he lost four games before the first time control.

Anyhow, even if I had won this match, I am not sure that I would have been able to call myself World Champion for long be cause the rules, created by Botvinnik, gave him the right to join the next World Championship contest and play for the title in a tournament with three participants; the present World Champion, his new challenger and Botvinnik himself I think that if you cannot defend your title in the same way that you get it you’re not a real World Champion.

By not winning the title I have put a shadow on my chess career and it is a little sad that I have had to read and hear for more than 40 years that I am not a good player.”

Long time after the match Bronstein said that he won his match before the adjournment whereas Botvinnik won after adjourning.

World Champion Botvinnik who since then had not too much sympathy for Bronstein wrote in his biography (My best games from 1925-1970): “Taking the fact I din’t play the last three years into account, the question should not be why Bronstein, who is inferior to me in both experience and positional understanding, did not lose the world championship match, but why he wasn’t able to beat an untrained player like me.”

In 1952, the Champion explained in CHESS the reason of his disappointed performance: “The main reason for my relative ‘reverse’ in this contest is the strength of my opponent. Bronstein successfully beat back my offensive in many games of the match and towards the end himself went over the active operations. Two games before the finish he gained the lead and, as a matter of fact, a draw in the 23rd, penultimate, game would have given Bronstein the title.

(About this 23rd game) For many moves that game proceeded without any particular advantage for either side, but shortly before the recess my adversary was over-hasty to win a awn and found hiself in a tight spot. Let me say when I adjourned the position at move 42, White’ advantage lies in the long-range power of his Bishops and the passivity of the Black’s Knights. The continuation is obvious enugh, and it was clearly seen by many of the chess fans who filled the Tchaikovsky Hall. 42. Bb1 fe4, 43 fe4 de4, 44.Be4 Kg7, 45 Bb7! wins. However I decided to try something more stronger and to make the whole maneuver more dangerous. I wrote down the move 42. Bd6. But as soon I returned home after the game I noticed Black now had a simple defense with 42… Nc6, 43 Bb1 Na7 intending to meet 44. ed5 ed5, 45. Ba2 b5 and Black can made good use of his doubled pawns with dangerous counter-chances which made me feel rather uneasy. At 5 p.m. play was resumed. After a sleepless night, it was an effort for me to concentrate, but Bronstein was so taken aback by the weak move I had seal, that he thought a full 40 minutes before making a move. This gave me the time to marshal my thoughts. The game continue 42…c6, 43.Bb1 Kf6? I have a sight of relieve my opponent didn’t find Na7!. I then made the move which was the culmination of my long night analysis 44. Bg3! and later won the game.”

In 1995 G. Sosonko Russian born and Dutch grandmaster and also chess historian published in NIC published and masterpiece interview on the “Patriarch” (nickname given to the oldest World Champion still in life). About his relation with Bronstein he said: “The first whom I severed all contact was Bronstein, after our match-he behaved outrageously. In the auditorium, directly opposite the stage, was the box of KGB, Dynamo, and all his supporters sat there. So when he sacrificed something, or on the contrary won a pawn, they all applauded,. And himself would make a move and quickly go behind the stage, then he would suddenly dart out and again disappear. In the auditorium there were laughter, and this hindered my playing. After the match we continued to say hello, he for me ceased to exist.”

Tom Furstenberg, a close friend of Bronstein and also co-author of his biography gave a interesting picture on what was happen around the controversial 23rd game: “The match was held in March, April and May 1951 and David surprised everybody, except himself, by more than holding his own against the considered ‘unplayable’ Botvinnik , the cool, hardworking, totally concentrated player who saw the opponent as the enemy to be overcome in the subsequent struggle.

Bronstein, utterly in love with the game, Chess Artist, romantic at heart, always looking for brilliant combinations and fantastic positions.

With the uncanny talent of being able to judge a position within a split-second David did not always need to calculate as much and as deeply as other grandmasters but usually intuitively found the right move in a specific position. During his match with Botvinnik the first thing he did in the morning was to go out and buy a newspaper to see the variations he was supposed to have seen! Often he bluffed, in similar fashion to but contrary to Tal’s combinations; David’s were usually correct, as subsequent analysis proved.

Many years later David wrote about this match: ‘I can never agree with the idea of fostering a hostile attitude to your opponent on the grounds that this will help you beat him. Of course, I, like any other player, strive to win and I am very happy if I succeed in overcoming my opponent by logic, fantasy, ingenuity, knowledge or sometimes even deep evaluation.

David prepared well for this match and surprised Botvinnik by playing the very openings Botvinnik himself liked to play! Tension during the match was high and became almost unbearable towards the end. With only two the scheduled 24 games remaining, David was leading by one point. It was then that he was summoned to the KGB’s private room at the theatre where the match was held. General Victor Abakumov, head of the KGB and also a member of the Dynamo Sports Club, introduced David to his wife and congratulated him with his beautiful win in the 22nd game. It was obvious t the majority of the chess fans wanted David to win the match because they all admired his beautiful and creative new style of chess.

The next morning David went, as had been his routine for every day of the match, for talk with Lydia Bogdanova, whom he had met some time before through a wonderful trick.

He had bought two tickets to the Bolshoi theatre, and on the evening of the performance, which was always sold out, he searched amongst the people who had no tick but wanted to go until he found a beautiful girl to go with him. He fell in love almost instantly! During their walk he indicated to her that it seemed that he was now very it to becoming the next World Champion. Would she like that? He was completely unnerved by her answer: ‘I really don’t care.’ It shocked him and in that state of mind he came to play the 23rd game, During that game David was obviously pre-occupied by what Lydia had told him. What did she mean? Did she really not care? It was hard to be but yet that is what she had said. In that confused state of mind David lost the game. Probably this was Lydia Bogdanova’s mistake which brought into question their intended marriage. Of course she wanted very much to be the wife of a famous chess player, yes, even the new World Champion.

However, the last game was a draw. The score was level and David became ‘Co-World Champion’ as Dr. Euwe put it…”

The pressroom was full with grandmasters and journalists few of them gave their views which were published in Chess 4/1951. R.G. Wade from New Zeeland: “There have been two outstanding characteristics an almost unparalleled determination by both contestants to play for a win, and the really difficult positions that both players seem to conjure up even in the games’ earliest stages. Some 20 years ago Capablanca, a famous world champion, complained that under its present rules chess was becoming easy for a Master to obtain a draw. I wish he lived to-day. Five games out of 12 had a definite result four have been won by Black. Further, due to the unusual stress of play, wins have been missed in at least two of the other games. Both players were typically well-trained beforehand. That is necessary, to endure a struggle lasting a couple of months. And yet already the constantly recurring difficulties set by the opponents have noticeably taken much out of the players.’’

Kotov grandmaster from Russia added: ‘‘That Black has won four times to White’s once only, shows the contestants’ high level of skill in defense and also their great theoretical preparedness, by which they were able to neutralize the advantage of the initial move, The games have contributed to chess theory suffice it to recall Bronstein’s Gruenfeld Defense innovation in the second game, or Botvinnik’s in the eighth, in the Slav Defense.’’

Keres: ‘‘Botvinnik is a player of profound strategic plant which he carries through with consistency, paying attention to all the subtleties and peculiarities of a position. Bronstein, on the contrary, is more inclined to tactical struggles, to acute positions fraught with unexpected combinations and sudden threats, Analyses of the games shows that the tactical struggle is prevailing this explains the unevenness,’’ Keres says that of all the games played so far, the eleventh impressed him the most. Botvinnik showed a high level of technique in the concluding stage of the seventh and Bronstein gave a model of stubborn defense in a difficult situation in the third.”

Gligoric: “Dr Botvinnik played with less assurance than Mr. Botvinnik. Bronstein was in no way pleasing to Botvinnik. In many ways they had very different natures. Botvinnik rarely appeared in public and always prepared himself in the peace of his own home. Bronstein enjoyed the turmoil of a chess club, playing lightning chess every evening. One was serious and concentrated, the other all nerves and fiery imagination. The outward manifestations of Bronstein’s vivacity were displeasing to the tranquil Botvinnik — Bronstein’s habit of standing and watching the board after every move he made, suite unconscious of the apparent condescension of his position far from the board, even the manner in which Bronstein drank his tea, holding his cup in both hands. Photos of the match show that at difficult moments Botvinnik frequently shaded his eyes with his hands so as not to see his opponent on the other side of the table, lest his appearance or behaviour disturb his concentration.

The match was transformed into an intensely complex struggle. Botvinnik had an iron will and great energy. He used his colossal experience and subtle strategy as well as he could, but none the less these unforeseen complications greatly exhausted hint The time-trouble, in which Bronstein was like a fish in water, and the psychological tactics, in which Botvinnik was faced with systems he himself used, brought him to the brink of catastrophe. But Bronstein showed certain levity and played poorly in the endgames, which cost him important points. By a supreme effort Botvinnik equalized the score with an endgame of genius in which he sacrificed a pawn without obvious purpose in order that much later — when a draw hovered over his head like the sword of Damocles — he could prove the advantage of his pair of bishops over his opponent’s knights. Only thus did he succeed in preserving his title.”