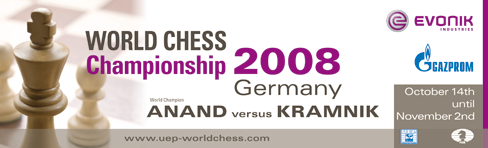

The World Championship match where Viswanathan Anand (India) will defends his World title against Vladimir Kramnik (Russia) took place in Bonn, Germany. The match consisted of twelve games, played under classical time controls, in the period from October 14 to October 30, 2008. The prize fund, which will be split equally between the players, was 1,5 million Euro including taxes and FIDE licensee fees.

The World Championship match where Viswanathan Anand (India) will defends his World title against Vladimir Kramnik (Russia) took place in Bonn, Germany. The match consisted of twelve games, played under classical time controls, in the period from October 14 to October 30, 2008. The prize fund, which will be split equally between the players, was 1,5 million Euro including taxes and FIDE licensee fees.

The reigning and undisputed World Champion Anand won his title in September 2007 at the World Championship tournament in Mexico City . Kramnik, who was undefeated in his three world championship matches, became second in this double round robin event. The organizer of the World Championship 2008 was Universal Event Promotion (UEP), which is located in Dortmund (Germany) and has received all rights for the event from FIDE. The main sponsors of the World Championship were Evonik Industries and Gazprom. The match consists of twelve games, played under classical time controls: 120 minutes for the first 40 moves, 60 minutes for the next 20 moves and then 15 minutes for the rest of the game plus an additional 30 seconds per move starting from move 61.

Game 1

Playing in the Queen’s Gambit Slav, Exchange variation, there was little by way of aggression from either side, as they preferred to wait and watch and spar in the first game.

Game 2

The first surprise was 1.d4 from Anand, and the second was that he was happy to allow a Nimzo-Indian Defence. Choosing 4.f3 (which leads back into a Saemisch) Anand took the usual advantage of 2 bishops, in return for a fractured pawn structure. By the time the game reached the middlegame it began to look as though Kramnik had an advantage, but just as quickly the game turned (22.Bb1!) and Kramnik surrendered his h pawn to untangle his pieces. However all this thinking sucks up time on the clock, and with only 3 minutes to reach move 40.

Game 3

The game featured a complicated Meran variation in which Anand unfurled a novelty in 14…Bb7! This pawn sacrifice helped Anand gain fluidity in the position. This was a departure for what fans feared would be a series of dull games

Kramnik’s 19.Nxd4!? muddied the waters and produced spectacular complications in which ended being favorable for black. Anand was up an entire hour during the match, but that lead melted away when Kramnik started to create nasty threats on the seventh rank. Anand returned the piece and was down two pawns, but his pieces were active and Kramnik’s king has no cover. Pressed for time, Kramnik made some crucial mistakes included the final with 33.Bd3?? when Anand pounced him with a finishing attack.

Game 4

Anand once again opened with 1.d4 although his choice of 3.Nf3 invited a Queens Indian Defence, rather than the Nimzo that was played in Game 2. Kramnik declined the offer and transposed into a Queens Gambit Declined. The players then reached a middlegame where White had a slight edge due to Black having an isolated d pawn, but as the position was well known to theory, Kramnik had little difficulty in maintaining equality. Once Kramnik was able to force d4, liquidating the d pawn, there was nothing left to play for and a draw was agreed.

Game 5

The players repeated Game 3 up until move 15, where Anand varied with 15. … Rg8, anticipating a possible improvement by Kramnik, who chose to sacrifice material in their earlier encounter. For the next 10 or so moves most commentators thought that Kramnik held the better position, but by move 24 Kramnik began to lose the thread of the position. Then on move 29 he grabbed a pawn that was definitely poisoned, and had to resign 7 moves later. Anand’s 34th move (Ne3!) was an elegant way to end the game.

Game 6

The game started as a Nimzo-Indian (as in Game 2), although this time Anand chose the more popular 4.Qc2. Kramnik offered the exchange of queens with 6. … Qf5 and although Black is left with doubled pawns, the position is considered easy to defend for Black.

Kramnik’s big mistake came on move 18 where he pushed to c5, rather than defend passively. It eventually lost him a pawn and from there it seemed to go downhill. He gave away another pawn but failed to generate enough compensation. Anand got a pawn to g7 and after some deft tactics was able to promote. Kramnik resigned a few moves after the first time control was reached.

@Chessbase

Game 7

The opening was a Queens Gambit Slav, which Kramnik had used in his 2006 match against Topalov. Anand (white) attempted to enliven the game with a pawn sacrifice on move 10, but Kramnik declined the offer. The queenless middle game saw a battle between bishop and knight (even with the rooks still on the board) but by move 35 all the pieces came off the board and a draw was agreed.

Game 8

Once again the game started with 1.d4 and Anand’s 4. … dxc4 resulted in Kramnik choosing the Vienna variation. This is a sharp line to play, although it can also result in a lot of minor pieces being exchanged. Interestingly enough Anand ended up with the a similar pawn structure he had in games 3 and 5 (black pawns on f7,fg and e6) and once again he chose to place his rook on the semi open g file. Nonetheless Kramnik had a small advantage in the position and Anand was forced to play exactly, to prevent Kramnik from dominating the centre with a push to f5. Kramnik could have forced a draw on move 30, but as this wasn’t the result he was looking for, he chose not to repeat the position a third time. However he wasn’t able to find any other way to improve his position and the game was drawn on move 39.

Game 9

Kramnik (as Black) chose to play the same opening that had brought Anand such success in games 3 and 5 (Semi-Slav). However Anand avoided going too far down the same road and chose the currently topical Anti-Moscow variation.

Kramnik spent much of the opening a pawn up (after taking on c4 and then hanging on with b5) but once Anand struck in the centre with 16.f4 the game really kicked into gear. Kramnik gave up his pawn advantage (19. … c5!), and another pawn as well, but this was only temporary and as the players headed towards the endgame, Kramnik was once again a pawn to the good. As the players approached the first time control, Kramnik even found a piece sacrifice (38. … a4) but unluckily for him, it wasn’t enough to win. Anand returned the piece at the right time and a drawn rook(s) ending was reached.

Game 10

The game started as a g3 Nimzo-Indian, and the players navigated their way through plenty of opening theory, before Kramnik played a novelty on move 18 (Re1). After that Kramnik increased his advantage by targeting Anand’s queenside, while Anand had a couple of pieces on the wrong side of the board. Despite attempts to scramble back Anand was ultimately too slow, and Kramnik’s push of the a pawn to a5 resulted in a decisive invasion of the Black position. Anand resigned on move 29.

Game 11

The game was surprising in that all the games had begun with 1.d4, but Anand trotted out his traditional 1.e4. There was an expectation that Kramnik will parry with his solid Petroff, but needing a win, he threw out the provocative Najdorf Sicilian. He mentioned in the press conference that he had “no clue at all about the theory.”

Anand changed the move order with 8.Bxf6!? gxf6 and 9.f5!? This didn’t appear to catch Kramnik off guard, but he went into a long think and actually got into a bit of trouble. Leading up to the final position, Anand had a clear advantage and had managed to thwart all of Kramnik’s tactical tricks. In a sign of class, Kramnik played 24…Be3, offered a draw which Anand immediately accepted. Kramnik congratulated Anand with a double-handed handshake.

After the match on Chess Base:

Anand: Though I would say with Vlady it is tough. You look at that match. I mean, when your first game goes like that, you think, you’ve done everything wonderfully and you think, you are a great match player. But in the games that followed I simply understood Vlady made some tactical errors. He challenged my preparation in an area (the Meran) where probably he didn’t pay any attention to this sub-variation I played against him. He simply walked into an ambush. And that explains the huge score differential. I’ll be honest. For the rest of my life with Vlady, our results have been more or less even. Tending one way or the other, but basically even. And after a lifetime of such equilibrium you are winning by three points after six games, it’s clear something went dramatically wrong with him. Now I feel you also have to be lucky. Vlady got in almost none of his preparation, I got in almost all of mine, and that happens just once in a while. He just walked into an ambush and that changed everything. The remaining games of our match did not go anywhere like that. And you have to remind yourself, this is probably normal and that was the exceptionally good day. You are not going to win that lottery every day.

Chess.com interviewed Kramnik:

Your reign as champion ended with the 2008 defeat to Vishy Anand. What went wrong in that match for you?

He was just better in everything! I was too slow. I had sensed that chess was changing, but I didn’t adjust. He used incredible, high-level computer preparation, certain tools I didn’t use. I didn’t think it was so important, and by the middle of the match, I realized it was basically over.

He’s an absolutely great player, and in fantastic shape, so even if I had been better prepared, I’m not sure I would beat him. It was just a bit of a pity because it was a fantastically organized match, a lot of interest, and somehow I didn’t manage to put up a real fight. The sporting element was more or less over after six games, and I felt a bit like I’d betrayed the sponsors and the public.

Everyone was expecting a tough, exciting match between two equals and it was quite one-sided. But you have to lose one day. I don’t consider myself some kind of genius, so frankly, even being world champion three times is more than I thought I would achieve. I had to lose it sooner or later, and Vishy was probably the best opponent to lose to.

In the Tribune of India:

For the first time in a decade, Anand found himself out of the top three in the world ranking. But nothing can keep Vishy down for long. A few days later he was the World Champion once again, regaining his No 1 ranking as well. He earned 13.6 Elo points from the three wins to overtake Bulgarian Grandmaster Veselin Topalov to log 2,796.6 points in the FIDE (International Chess Federation) ranking. His next aim is to tote up 2,800 points, but he will have to do a lot of catching up to equal Gary Kasparov’s all-time record of 2,851 Elo points. Kasparov is still the highest-ranked GM in the history of the game, and it will be hard, even for Anand, to emulate Kasparov.

At Bonn, the sharp-witted Anand gave a crushing reply to boastful Kramnik, by beating him with 6.5-4.5 points to retain his world title in their 12-round clash with one game to spare.

Anand has become the only Grandmaster to win all three formats of world chess titles — the 128-player knockout championship (2000 Tehran, now discontinued), the eight-player knockout round-robin championship (2007 Mexico City) and the traditional match-play. He was also the first player from outside the Soviet bloc, after Bobby Fischer in 1972, to win the world title.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Total | |

| Kramnik, V | ½ | ½ | 0 | ½ | 0 | 0 | ½ | ½ | ½ | 1 | ½ | 4 ½ |

| Anand, V | ½ | ½ | 1 | ½ | 1 | 1 | ½ | ½ | ½ | 0 | ½ | 6 ½ |

This match definitively settles the question of who holds the Title. Anand has now become the Undisputed 15th World Chess Champion.